2020 Reading Roundup: Forests and Miniaturists

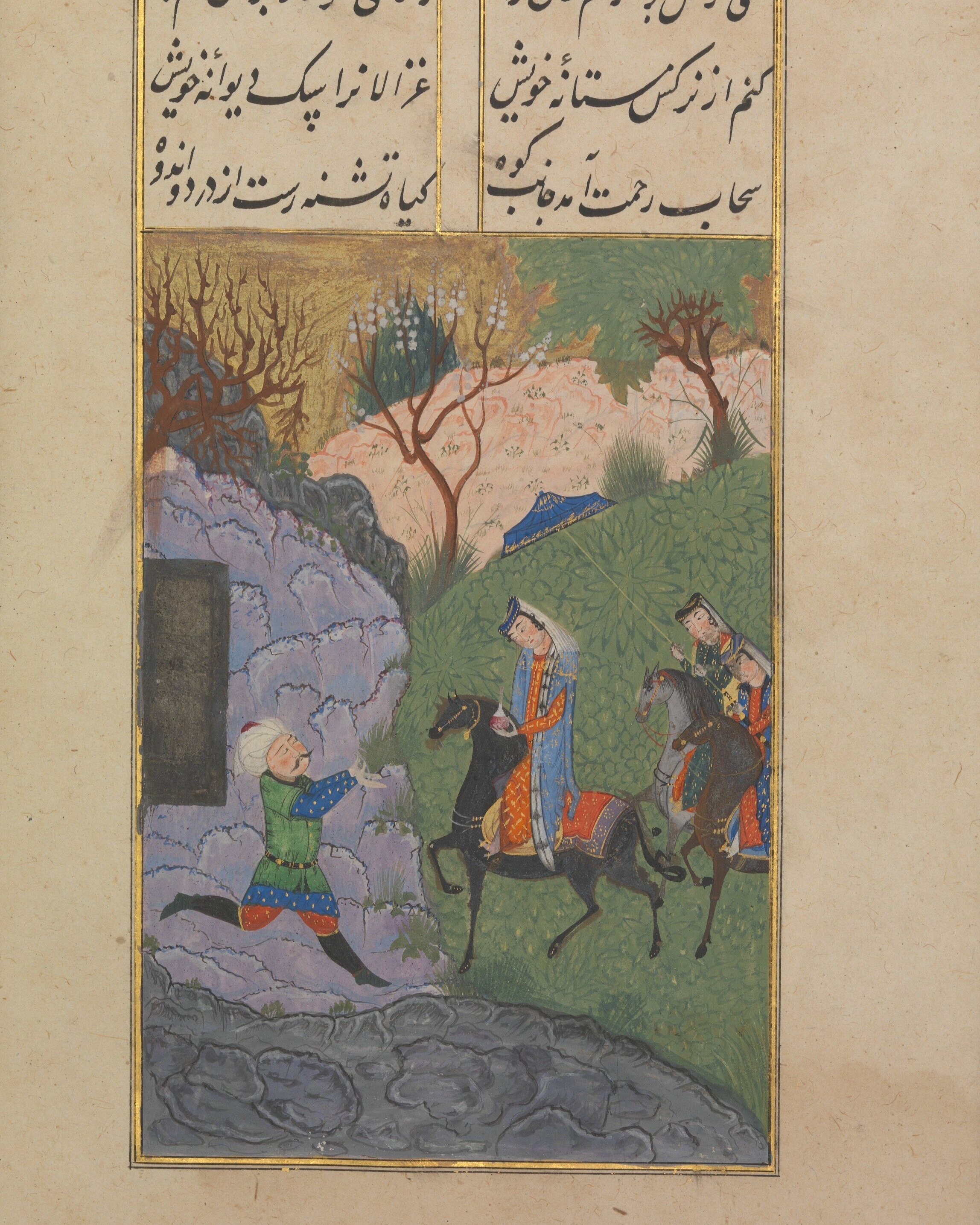

“Khusrau and Shirin,” illumination by Ottoman artist Suzi, c. 1499. Public domain image from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Orhan Pamuk thinks that Ottoman miniature paintings are amazing. Richard Powers thinks that trees are amazing. They wrote long, structurally innovative novels about their obsessions, which won prizes and captured the Zeitgeist. (The early 2000s were ripe for an ambitious novel about the complicated relationship of Islamic culture and Western culture, just as the late 2010s were ripe for an ambitious novel about environmentalism.) And… I really don’t get the hype about either one.

My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk

My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

I like the concept of My Name is Red so much more than I actually liked reading it. Orhan Pamuk is the first Turkish author to win the Nobel and received lots of attention in the early 2000s for writing complex novels about conflicts between the Islamic world and Western culture. Better yet, My Name is Red initially seems more fun and pulpy than your typical Nobel fare: it’s an Ottoman-era murder mystery whose first chapter is narrated by the corpse!

Crime fiction can provide an excellent framework for novelists to explore society, and at first, Pamuk’s evocation of 1590s Istanbul is spellbinding. He conjures up places ranging from a rowdy coffeehouse to the Sultan’s palace, while setting up an intriguing mystery. The murder victim, an artist nicknamed “Elegant,” seems to have been killed because of his involvement with a secret project that blended Western artistic techniques with traditional Islamic illumination styles.

But what first seemed so fresh and lively quickly becomes tedious. Pamuk’s ornate style, full of detailed lists (“He was intently observing my long paper scissors, ceramic bowls filled with yellow pigment, bowls of paint, the apple I occasionally nibbled as I worked, the coffeepot resting on the edge of the stove in the back, my diminutive coffee cups, the cushions…”) and meticulous descriptions of Ottoman miniature paintings (“To convey the passion and woe of the lovers, the rocks on the mountain, the clouds, and the three noble cypresses were drawn with a trembling grief-stricken hand…”) slows down the narrative momentum. Over and over, the various narrators pontificate on the differences between Islamic art, with its reverence for tradition, and Western art, with its emphasis on individual style. But these themes get repeated without being developed. Maybe this is supposed to echo the “Islamic” love of repetition and stasis. Maybe I am too Westernized to appreciate the book on its own terms? At any rate, it didn’t work for me.

I was also disappointed in the handling of the mystery plot. Not only does it get overshadowed by the philosophical concerns, it isn’t particularly complex. The three murder suspects—artists nicknamed Butterfly, Olive, and Stork—have chapters where they speak in their own voices, but there are also chapters told from the (unidentified) murderer’s perspective, where he dares you to analyze his words and try to figure out which man he is. In the hands of a novelist who cared more about murder-mystery pleasures, this could be a really clever idea. But the three artists are not characterized very distinctly, and at least in Erdag Göknar’s English translation, all of their voices sound the same.

There is some beautiful writing and intriguing ideas here, particularly in the chapters narrated by inanimate objects. (Think a 1590s Ottoman version of McSweeney’s “Short Imagined Monologues.”) But I found myself wishing that Pamuk hadn’t done quite so much historical research… or that Elegant’s corpse had just revealed who murdered him in chapter 1 and gotten it over with.

The Overstory by Richard Powers

The Overstory by Richard Powers

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

The Overstory is a novel with such a strong agenda behind it—to promote environmentalism and the preservation of forest ecosystems—that disliking it could be misconstrued as hating trees and the planet. So I feel like I should start this review with my tree bona fides. I love forests; I grew up in the magnificent Pacific Northwest bio-region; I was ecstatic when my local Botanical Garden reopened after two months of pandemic closure this spring. Even if I couldn’t hug any of my human friends for fear of coronavirus, at least I could go hug a redwood.

But none of that means I have to overpraise The Overstory.

True, the book begins promisingly, with a dazzling set-piece chapter about the history of the American chestnut and the 150-year history of a Norwegian immigrant family. More short-story-like chapters follow, each telling the story of an American in the second half of the 20th century who has a connection to a special tree. This seems to be the most universally acclaimed part of the book, and the stories are well-written, but they do get same-y after a while: coming of age, fathers, children, tragedy, trees.

In the middle section of the book, several of these characters meet up and become radical environmentalists—first dwelling in redwood trees to prevent them from being cut down and then, when that doesn’t work, turning to eco-terrorism. I think this was my favorite section, because it most resembled a conventional novel: a suspenseful plot, caused by characters taking action to achieve their goals.

But we’re not supposed to desire the pleasures of a conventional story—we’re supposed to be paying attention to the meta-narrative, the overstory. So after the eco-terrorism section, the book gets diffuse and disparate again, this time with some unnecessary postmodern trickery added on. Which of the two conflicting descriptions of a scene reflect what “really” happened? Is one of the central characters “real” or a product of two other characters’ imagination? What does any of this have to do with forest ecology?

Richard Powers peppers the narrative with scientific facts and rhapsodic musings about trees, to an extent where I wondered whether he really should've written a work of creative nonfiction rather than a novel. Throughout, there are lovely sentences (“Five interstates lead west, the fingers of a glove laid down on the continent with its wrist in Illinois”), but also a heaping dose of the most irritating male-author nonsense since fellow Pulitzer-winner

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

(“She sails off across the floorboards, her tits glowing like precious pearls”). Powers wants us to transcend our selfish human limitations and accord trees the admiration, protection, and wonder that they deserve. But he seems to have more respect and understanding for forest ecosystems than he does for his female characters.